‘Prehistory holds up a challenging mirror to us’

Leiden alumnus Luc Amkreutz is a curator at the National Museum of Antiquities. His exhibition about the submerged landscape of Doggerland highlights what we can learn from prehistory. ‘Just like the people of Doggerland, we are confronted with climate change, but we are responsible for the speed of the current change.’

Following its enforced closure for several months during the lockdown, the National Museum of Antiquities reopened its doors to the public in June this year, and Luc Amkreutz is clearly glad to see it. In his study, which is located at the back of the museum in Leiden and filled to bursting with archaeology books and research material, the curator reflects on the past year. ‘I prepared two exhibitions, about Doggerland and Malta, and because I had to work with the objects themselves I continued to spend quite a lot of time at the museum. At one point we weren’t sure if we’d be able to open. The exhibitions were supposed to start in April – everything was ready but no one could come in. It was very surreal.’

A lost world in the North Sea

Fortunately, the museums are now open again and the exhibition Doggerland: A lost world in the North Sea is attracting a lot of interest, not least because of its relevance to climate change. Large parts of this area, now submerged beneath the North Sea, were once dry land. During the ice ages it was a cold steppe landscape where Neanderthals hunted mammoth, rhino and deer; their bones still come up in fishing nets to this day. After the last ice age, modern humans moved into what was then a wet and heavily forested area. ‘These inhabitants of Doggerland began to experience the effects of large-scale climate change about 11,000 years ago,’ Amkreutz explains, ‘just as we are now. Melting ice caused sea levels to rise, and after an enormous tsunami Doggerland soon vanished beneath the waves.’

‘The people of Doggerland were living in a drowning landscape, just as we are today’

A message to climate change deniers

Visitors leave the exhibition with an emphatic message: ‘Just like the people of Doggerland, we are confronted with climate change, and this time our own actions are playing a role’ says Amkreutz. ‘If we don’t share that message, the discussion will be hijacked by climate change deniers who say that the climate has always changed. Of course the climate has always fluctuated, but this huge acceleration is down to us.’

Amkreutz sees this exhibition at the National Museum of Antiquities as a first. ‘This is the first real retrospective about Doggerland, the biggest archaeological site in Europe. The finds began to emerge in the 1950s and ’60s: caught in fishing nets, washed up on the coast or sprayed among reclaimed sand from the sea bottom.’ The sand transported to the Maasvlakte area near Rotterdam and the Zandmotor near Kijkduin yielded a spectacular increase in the number of finds.

A sneak peek into the Doggerland exhibition

Due to the selected cookie settings, we cannot show this video here.

Watch the video on the original website orMore recognition for prehistory

Curator Amkreutz wants to achieve greater recognition for prehistory, which makes up more than 99% of our history. ‘I don’t want to idealise prehistory, but it does hold up a challenging mirror to us: prehistoric communities lived much more in balance with their environment than we do now. We think we can completely shape nature into an environment that serves us.’

Another example is the constant flow of migration in history. ‘The first modern humans in Europe probably had a darker skin colour, and the first farmers were probably also dark-skinned. Blonde Dutch people are probably largely descended from migrants who arrived from Russia around 5,000 years ago. Knowing that helps us find our place as inhabitants of Europe. Prehistory puts things into perspective.’

A museum for a bedroom

Amkreutz studied Archaeology at Leiden and obtained his doctorate here. What made him choose Archaeology? ‘I’d spent a year studying Law in Maastricht,’ he remembers, ‘but during that year I loved to read books about archaeology in my free time. I grew up in Sint Geertruid, a village in Limburg near a flint mine that’s thousands of years old. The mine was used by the successors to the earliest farmers in Europe. I found all kinds of flint tools and fossils in the fields around Sint Geertruid. I took them home and built a little museum in my bedroom.’ That interest waned during his teenage years, and for practical reasons Amkreutz decided to study Law. ‘Actually, it was only then that I started thinking about what I really enjoyed. Professor Louwe Kooijmans – who later became my supervisor – spoke so enthusiastically at a Leiden open day that I switched to Archaeology.

‘Of course there were setbacks, when after two weeks of digging all we found was a dirty T-shirt. But that’s all part of the experience’

Rooting around on a Neanderthal site

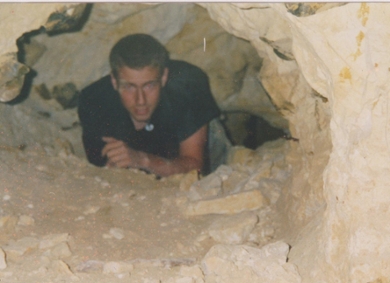

So what did Amkreutz think of his course? ‘I felt right at home. Probably thanks to my personal interest and my roots, I felt the strongest connection with European prehistory. I was a very keen student: I’d think I hadn’t done well and then find I’d scored nine out of ten.’ He spent entire summers with archaeologists, working on sites in the Oostvlietpolder and near the towns of Sittard and Oss. ‘I absolutely loved excavating pits and potholes from the settlements of the first farmers in the Netherlands, and spending the winter helping to dig a Neanderthal site in Belgium. Of course there were setbacks, and after two weeks of digging in the clay all we found was a dirty T-shirt from a dig two years earlier. But that’s all part of the experience. It’s exciting to be so physically involved with the past, and to make a discovery yourself.’

PhD research on the first farmers

As soon as he graduated, Amkreutz was able to start his PhD research in Leiden. His research focused on the settlements of Europe’s first farmers and the process of neolithisation: the transition to farming. ‘The research just grew and grew until it was a struggle to get it all down on paper.’ He indicates a thick black volume on a bookshelf: ‘There it is! Of course, the key is to narrow down your topic. I started working here at the National Museum of Antiquities as a curator in 2008, after four years of PhD research, and for a long time after that I had to write my dissertation in the evenings. That was an important lesson for me: try to finish one thing before you start something new.’

A barnacled cigarette lighter

His work as a curator is very varied, from creating exhibitions and communicating with the public to conducting and facilitating research. ‘There are a lot of finds in our depot that have never appeared in a publication,’ he explains, ‘as well as finds that deserve new research. Many artefacts were excavated between 1890 and 1940, and now there are new techniques we could use to study them. I’m itching to do that research, but of course I can’t do everything myself.’

Getting back to Doggerland: will visitors see any of his own finds in the exhibition? He laughs. ‘Yes: a few bits of flint, amber and shells from the last interglacial period. And the last display case contains a cigarette lighter covered in barnacles. I found it on the Zandmotor near Kijkduin. The lighter is an example of the kind of rubbish we throw in the sea today.’

Text: Linda van Putten