The ethics of returning colonial photography

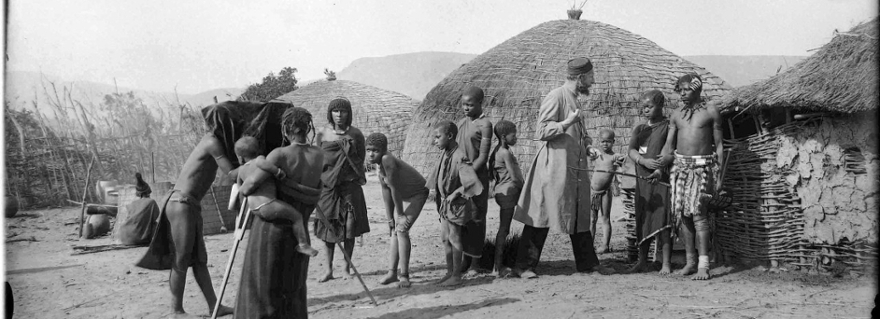

Is it ethical to freely redistribute photographs taken in colonial contexts, historically and today? Christoph Rippe, PhD-candidate Cultural Anthropology, suggests that people might not have been always fully aware of what happened to their photographs after they were taken. 'But nowadays, with the proper consent, these images can be enriching for the life and the history telling of people in South Africa under certain circumstances.' In his study, Rippe looked at how a vast media network evolved around the commercial photographic studio at Mariannhill Monastery and the mission station Centocow in South Africa from the 1880s until today. His thesis shows that different cases ask for different evaluations.

“Giving back” or returning looted art has been a hot topic lately. For the broader public, this became visible in 2017 when French president Emmanuel Macron made his intentions public to return objects from French museums to Africa. Last year Germany followed by deciding to return two statues to Nigeria, better known as the Benin’s bronzes. And last month the Belgium Africa Museum announced that it will return stolen artworks to the Congo. But what about photographs taken in colonial settings? How do deal with them? They are a different story, Rippe explains. ‘Photographs can be reproduced, museums can make copies to give away and keep the original photograph. But if you bring old photographs to people who have never seen any photographs from the time of their great grandparents, it has a great impact. As a researcher, it gives you a certain power that is, maybe, unjustified. That might not be ethical to do.”

Lobbying to continue the research

Rippe started his PhD research in 2009 out of general interest in photographs. ‘Photographs are often undervalued: by private people, by the common media and also scientifically. Photos appear to be so common, we are all very used to seeing images. But when looking closer, you will see how peoples’ actions may be influenced by the presence of a photograph.’ Rippe finished his dissertation in 2019. But due to COVID-19 his defense was delayed for 15 months. This was not the only delay that he faced. Initially considerable lobby work was required to gain access to the respective archives of the Mariannhill Mission congregation.

Mariannhill Mission photo collection

Mariannhill Monastery was founded in 1882 by German Catholic Trappist monks in South Africa. Around 1900, the Monastery had almost 300 members and was independent of the local economics because they had their own carpenters, shoemakers, bakers, etc. And they had a commercial photo studio. The photo archive that remains nowadays, consists of approximately 3.000 individual photographs. Historically there must have been many more because the studio was also a commercial photo studio where people could get their portrait taken. Rippe looked at these photos for his PhD, not only in the archives of the Mariannhill Mission itself, but also in European museum archives. Many of the photographs ended up in ethnological museums. This turned out to be a very useful source for Rippe, because the museums kept track of how the photographs were evaluated and some of the museums still have the original correspondence with the missionaries from that time.

“This idea of a network and of looking at relations in, through and of photographs, allow you to understand what the social role of photographs can actually be.”

Photos can only be studied considering interconnectedness

To show the complexities behind the question whether it is ethical to freely redistribute photographs taken in colonial contexts, Rippe takes a grass-roots perspective and argues that photographs produced by missionaries, like all colonial photographs, must be studied by considering their interconnectedness with other media, the exhibitionary complex they depend on and discourses and communities that produced, used and consumed them. To show the photographs’ ongoing relevance for stakeholders in both South Africa and Europe, and possible ways of dealing with them today, Rippe followed their intermediary role over time and in between other images, spaces, objects, and subjects. Rippe: “This idea of a network and of looking at relations in, through and of photographs, allow you to understand what the social role of photographs can actually be.”

The defend of Christoph Rippes dissertation “The Things in Between: Photographs from the Mariannhill Mission in KwaZulu-Natal and Other Objects in Situations of Intermediality” takes place on 1 July 2021.