Leiden Classics: Bibliotheca Thysiana, a 17th century time machine

From once controversial scientific works and historical bibles, to personal shopping lists and clothing bills. The 17th-century Bibliotheca Thysiana and the archive of the collector Johannes Thysius exhibit both the intellectual and everyday life as it was three hundred years ago. Now a brand-new digital inventory has been developed, which will enable us to make new discoveries.

The first public library

Arent van ‘s Gravesande

designed the impressive

structure in the

Dutch Classicist style.

It’s one of those rare locations where time seems to have genuinely and completely stopped. The corner of the Rapenburg and the Groenhazengracht in Leiden has been the location of the country’s first public library building since 1657. The absence of a proper inventory has induced a drowsy existence that has persisted for years, but all that is about to change.

New digital inventory

A new inventory for the Thysiana has  been available through the University Library’s since early 2014, but it’s only finally becoming clear what treasures can be found in the 15 meter long archive that covers the library and the private collection of Johannes Thysius (1622-1653) and his family. ‘It offers us a way to discover a lot more about them,’ curator Paul Hoftijzer explains. He is Leiden’s extraordinary Professor of the History of the Dutch Book in the Early Modern Period.

been available through the University Library’s since early 2014, but it’s only finally becoming clear what treasures can be found in the 15 meter long archive that covers the library and the private collection of Johannes Thysius (1622-1653) and his family. ‘It offers us a way to discover a lot more about them,’ curator Paul Hoftijzer explains. He is Leiden’s extraordinary Professor of the History of the Dutch Book in the Early Modern Period.

Descartes lived three door down from here

Hoftijzer emphasizes the rich diversity of the collection: ‘Thysius had very broad interests. He collected a wide range of academic works: from classical texts and medieval manuscripts to scientific revelations of his own age. He also owned, for instance, the works of the controversial philosopher Descartes, who was also living on the Rapenburg at the time, three doors down from here.’

Original volumes

Book historian Erik Kwakkel, from Leiden, calls the collection a ‘time machine’: ‘Bibliotheca Thysiana somehow transports a complete collection of 17th-century books to the modern age, while keeping its original character intact. The collection also provides us with insights into the literary tastes of the educated elite from that period.’ The large number of original book covers from the early modern period makes this collection especially valuable for Kwakkel’s own research.

Hidden contents

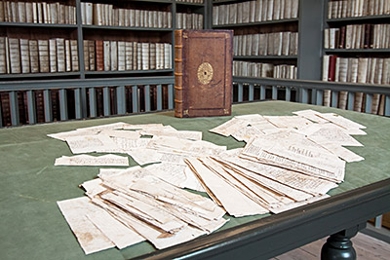

These book covers often contain an extra treat for medievalists. Kwakkel: ‘Bookbinders tended to use cut-up bits from old manuscripts when binding their books. The Thysiana book covers were filled with hundreds of medieval scraps of paper and fragments of parchments, including a section of the archive of a German count.’ These materials were unearthed during a course taught by Kwakkel and Hoftijzer, and contain information that is rarely preserved. For while containing official documents, these scraps of paper also include shopping lists and notes asking someone to bring back some roses from the countryside.

A historical goldmine

Aside from his library, Thysius also preserved his own family’s archive, including vast numbers of letters, travel journals and accounts. ‘This has allowed us to chart what he purchased and how much he spent on his clothing for example, including the ‘Japonese robe’ that was fashionable among students at the time. This archive contains lots of information about everyday life that has usually been badly documented, or even lost. It’s truly a goldmine for historians.’

Jan Thijs

There’s a tragic story behind the foundation of this remarkable library. Jan Thijs, the son of a wealthy merchant, became an orphan at the age of twelve. He was taken in by his uncle Constantin l’Empereur, Professor of Oriental Languages in Leiden, who encouraged his love for books. Thysius himself studied law in Leiden, and would also obtain his doctorate there. Students from that time had the habit of Latinising their names, so Jan Thijs became known as Johannes Thysius while a student.

His last will and testament

Unfortunately, the young bibliophile died at the age of 31. On his deathbed, Thysius decided that his personal library was to be used ‘to publicly serve education.’ The testament in which this was recorded is still kept in a small chest inside the library. At the time, his collection consisted of approximately 2500 books and thousands of pamphlets, though the library’s collection has been slightly expanded since his death. His testament also reserved a large sum of money to construct a library to house his collection.

Requesting the books

As both the collection and the library itself are valuable and delicate, the historical structure isn’t always open to the public. Curious people are welcome to make an appointment to visit the library, while the books can be requested through the University Library’s catalogue. The books will then be taken to the UB, where they can be studied. Hoftijzer: ‘We’re trying to respect Thysius’s last wish to keep his collection open to the public. But at the same time we have to protect both the structure and the collection from decay. It’s a precarious balance.’